— English version below —

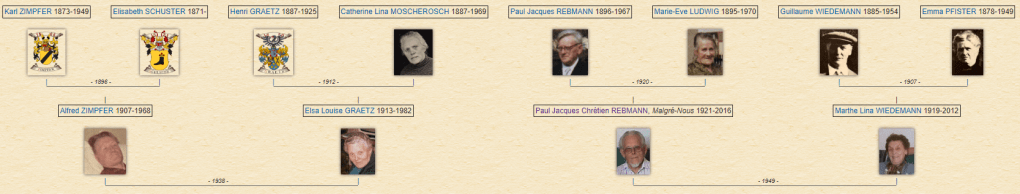

Aujourd’hui j’ai envie de vous parler de l’impact de la seconde guerre mondiale sur ma famille, et plus précisément sur la génération de mes grand-parents qui fut touchée de plein fouet, de part leur âge (de jeunes femmes et hommes en 1939/1940) et la localisation géographique, à savoir l’Alsace, et plus spécifiquement le Bas-Rhin.

Outre la vie d’Alfred ZIMPFER, Elsa GRAETZ, Paul REBMANN et Lina WIEDEMANN entre 1939 et 1945, je me suis aussi penché sur la vie de Henri GRAETZ et Charles GRATZ, les frères de ma grand-mère paternelle, pour lesquels j’ai retrouvé des informations intéressantes, en particulier pour Henri GRAETZ à qui je vais devoir consacrer un article, tant sa vie fut « particulière ».

Les « Malgré-Nous » :

L’expression « malgré-nous » désigne les Alsaciens et Mosellans incorporés de force dans la Wehrmacht, armée régulière allemande, durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, que ce soit dans la Heer (armée de terre), dans la Luftwaffe (armée de l’air), dans la Kriegsmarine (marine de guerre), ou encore dans la Waffen-SS. Le pendant féminin a été constitué par les malgré-elles.

L’Alsace (moins l’arrondissement de Belfort), une partie de la Lorraine — le département de la Moselle dans ses limites actuelles — et quelques villages du département des Vosges furent cédés à l’Empire allemand au Traité de Francfort, après la défaite française de 1871 laissant aux populations pendant quelques mois le choix d’ “opter” pour la France. Les populations de ces contrées qui restent sur place – notamment pour garder une présence française en zone annexée – se sont ainsi retrouvées sujets de l’Empereur germanique et soumises aux obligations et usages des ressortissants du nouveau Reich. À la fin de la guerre, en 1918, après 4 ans de dictature militaire, de brimades et de destructions volontaires, la population d’Alsace-Moselle n’éprouve plus la moindre sympathie pour l’Allemagne et fait le dos rond en espérant une paix prochaine. Ils redeviennent également français.

Le problème est radicalement différent en 1942, tant sur le plan sociologique que sur le plan juridique. D’un point de vue humain, les jeunes appelés Alsaciens et Mosellans ne sont pas nés Allemands ; ils sont majoritairement restés « Français de cœur » et n’ont pour la plupart pas opté pour obtenir la nationalité allemande, qui leur a été octroyée d’office au nom du Volkstum.

D’un point de vue légal, l’annexion de facto des trois départements français par l’Allemagne nazie n’a pas été ratifiée par le droit international ni d’ailleurs par aucun traité entre la France de Vichy et l’Allemagne .

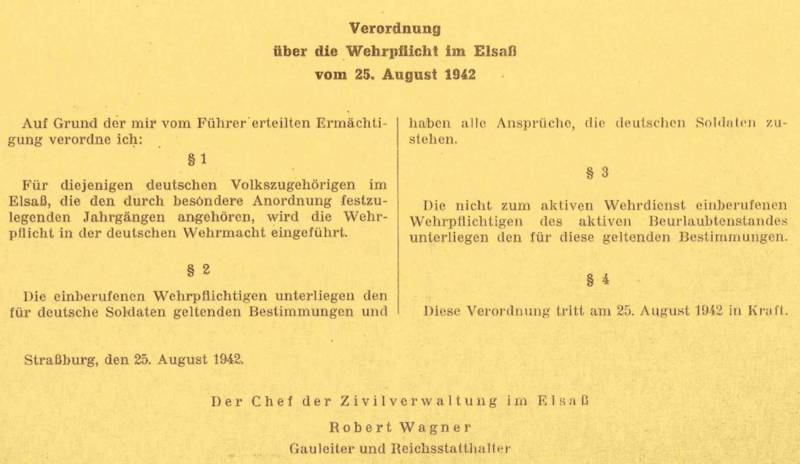

Bien que le terme « malgré-nous » apparaisse déjà en 1920, après la Première Guerre mondiale, lorsque des associations d’anciens combattants alsaciens et lorrains de la Grande Guerre emploient cette formule pour mettre en avant le fait qu’ils avaient dû se battre « malgré eux » dans l’armée allemande contre la France, les premiers véritables « malgré-nous » ont été incorporés de force par l’armée allemande à partir d’août 1942.

Quand l’armistice du 22 juin 1940 est signé, les cas de l’Alsace et de la Moselle ne sont pas évoqués. Ce territoire reste donc juridiquement français, bien qu’il fasse partie de la zone militairement occupée par l’Allemagne.

Le régime nazi l’annexe de fait au territoire allemand, par un décret du 18 octobre 1940 signé par le Führer Adolf Hitler qui en interdit la publication.

Le gouvernement de Vichy se borne à des notes de protestation adressées aux autorités allemandes de la commission de Wiesbaden, mais sans les rendre publiques, craignant les réactions allemandes : « Vous comprenez, disait en août 1942 le maréchal Pétain à Robert Sérot, député de la Moselle, les Allemands sont des sadiques qui nous broieront si, actuellement, nous faisons un geste. ». D’ailleurs ces notes restaient toujours sans réponses.

Le bruit se répand alors qu’une clause secrète avait de nouveau livré l’Alsace-Lorraine à l’Allemagne, à cette différence près que les trois ex-départements français ne formaient plus une entité propre, comme c’était le cas lors la précédente annexion. Ainsi, le Bas-Rhin et le Haut-Rhin deviennent le CdZ-Gebiet Elsass, territoire rattaché au Gau Baden-Elsaß ; tandis que la Moselle devient le CdZ-Gebiet Lothringen, territoire rattaché au Gau Westmark le 30 novembre 1940.

Jusqu’en août 1942 cependant, si on multiplia les organisations paramilitaires, où la population des jeunes, était obligée de s’inscrire, on s’abstint de l’ultime transgression juridique, la mobilisation obligatoire dans l’armée allemande. Mieux encore, l’Allemagne proclamait qu’elle n’avait pas besoin des Alsaciens-Mosellans pour gagner la guerre, qu’elle espérait bientôt terminée et victorieuse. « Nous n’avons pas besoin des Alsaciens pour gagner la guerre, disait un orateur de la propagande, mais c’est pour l’honneur de votre pays que nous tenons à vous avoir dans nos rangs ».

Les services de Goebbels n’en firent pas moins une propagande active pour inciter les jeunes Alsaciens et Mosellans à s’engager, mais sans le moindre résultat. Seuls les fils des fonctionnaires allemands présents semblent avoir répondu à l’appel, mais ils furent moins d’un millier pour les deux départements alsaciens. Le gauleiter Robert Wagner, qui était responsable de l’Alsace, était persuadé que ceux qu’il considérait comme des frères de race nouvellement reconquis entendraient vite l’appel de leur sang et se sentiraient rapidement allemands ; constatant le nombre infime d’engagés volontaires, il conclut — non sans cynisme — que les jeunes hésitaient à entrer dans l’armée allemande « par peur de leur famille » et qu’ils seraient heureux de s’y voir forcés.

Au printemps 1942, à Vinnitsa, il persuada Adolf Hitler, au début fort réticent, d’introduire le service militaire obligatoire en Alsace, ce qui fut fait officiellement le 25 août 1942.

Le « Malgré-Nous » Paul REBMANN & Lina WIEDEMANN :

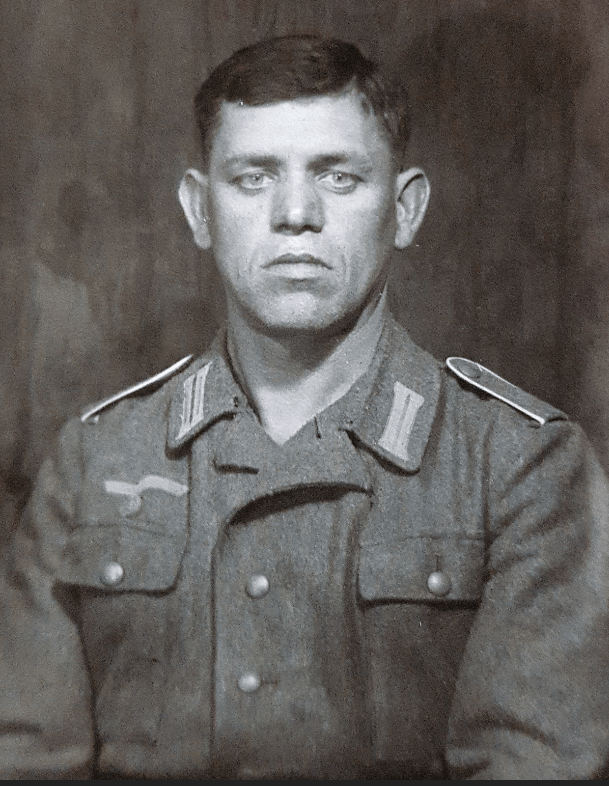

Mon grand-père maternel Paul Rebmann fut touché de plein fouet par cet ordre d’incorporation obligatoire, et se retrouva incorporé dans l’armée du IIIe Reich le 22 Mai 1943, pour combattre sur le front Russe.

De facto, bien qu’il fréquentait déjà ma grand-mère Lina Wiedemann, le mariage n’était plus à l’ordre du jour à partir d’Août 1942, et encore moins en Mai 1943.

Il avait bien tenté de fuir le Bas-Rhin vers le nord ouest (Sarrebourg) dès Mai 1940, en vélo, avec son cousin Georges Brenner, accompagné du curé de Bischwiller, comme il le raconte au début de son livre « Mémoires de Guerre », mais sans succès. L’armée allemande était déjà arrivée aux portes de Saverne, et ils durent rebrousser chemin, en entendant au loin les tirs des canons d’artillerie.

Dès son incorporation en Mai 1943, il fut envoyé sur le front Russe, dans un secteur correspondant aujourd’hui à la Bielorussie. Entre fin Octobre et début Novembre 1943, il était station non loin de Moguilev, la Wehrmacht essayant de prendre un village à cette endroit, sous le feu des « orgues de Staline ».

Comme il le relate dans ses mémoires (traduction de l’alsacien par Claudine Drago et repris dans l’excellent livre « Nous étions des Malgré-Nous » de Laurent Pfaadt) :

« Nous étions très tôt le matin, à une centaine de mètres d’un village. Tout le monde courait, je me sentais terriblement seul. J’entendais les balles siffler. On tirait de partout, à gauche, à droite. Il y avait des corps allongés au sol. Nos supérieurs ne se préoccupaient pas des corps, de toutes ces vies perdues, l’essentiel pour eux était de prendre d’assaut le village ! Des Russes occupaient les maisons et mouraient sous nos yeux. Malgré l’horreur, nous étions affamés, mais aucun ordre n’était donné pour pouvoir manger nos rations. J’avais tellement faim que je ne pouvais m’empêcher de fouiller le sac à dos d’un Russe mort pour y dénicher le moindre morceau de pain sec. J’avais honte mais on ne peut pas s’imaginer de quoi l’être humain est capable dans un moment pareil ! »

Peu de temps après, il réussit à s´évader, et à déserter la Wehrmacht, pour se rendre aux Russes, et à partir de décembre 1943, il se retrouva au Camp de Prisonniers 188 de Tambov, qu’il ne quittera qu’après la fin de la guerre, fin novembre 1945.

Une fois libéré de Camp de Tambov, Paul fera un passage à Berlin, pour raison médicale, afin de reprendre suffisamment de force pour pouvoir rentrer dans sa famille. En arrivant à Berlin, Paul ne pesait plus que 36,5 kg. C’est finalement le 26 Novembre 1945 qu’il arrive au centre militaire de Reuilly, et que M. Roussillon a envoyé un télégramme à Paul Rebmann père pour le prévenir du retour de son fils.

Pour les détails, merci de consulter l’article : PAUL REBMANN (1921-2016) : MON GRAND-PÈRE MATERNEL

Alfred ZIMPFER & Elsa GRAETZ :

Concernant mon grand-père paternel, je n’ai trouvé aucun document qui tendrait à montrer qu’il ait été actif durant la 2ème guerre mondiale, ni en tant que « Malgré-Nous », ni dans la résistance.

Peut-être que le fait qu’il était déjà marié depuis 1938, et père de famille, a fait en sorte de lui épargner cette incorporation obligatoire.

Pour les détails, merci de consulter l’article : ALFRED ZIMPFER (1907-1968) : MON GRAND-PÈRE PATERNEL

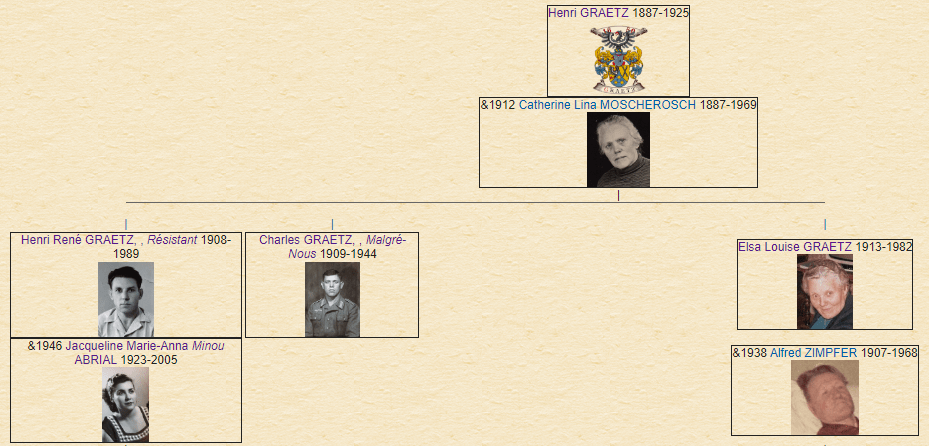

Le Résistant Henri GRAETZ et le « Malgré-Nous » Charles GRAETZ :

Les deux frères de ma grand-mère paternelle ont eu un parcours diamétralement opposé durant ce conflit.

Tout comme mon grand-père Paul Rebmann, le jeune Charles GRAETZ, né en 1909 à Bischwiller, fût après Août 1942, incorporé de force dans la Wehrmacht et également envoyé sur le front Est.

Cependant, il eut beaucoup moins de chance que mon grand-père, vu qu’il fut tué le 4 Novembre 1944, en Pologne, près du village de Pokrzywnica.

Selon son dossier sur « Mémoire des Hommes », il a été reconnu comme « Mort pour la France » à 35 ans.

Son frère Henri GRAETZ a eut un parcours beaucoup plus atypique, puisqu’il a servi dans la résistance, mais pas en France.

Selon les données trouvées il résidait avant le début de la guerre, à Saïgon (Hô-Chi-Minh-Ville), en Indochine Française.

En Décembre 1941 il a eut un ordre de mobilisation militaire, engagé au sein des Forces de la France Libre. Son affectation principale : la résistance intérieur au sein du « réseau Graille » (Source : Liste Ecochard).

Visiblement il s’en sort indemne, puisqu’on retrouve sa trace, de part son mariage en 1946, toujours à Saïgon, avec Jacqueline ABRIAL, et son décès en 1989 à Nyons dans la Drôme.

Today I’d like to talk about the impact of the Second World War on my family, and more specifically on my grandparents’ generation, which was hit hard by the war, due to their age (young men and women in 1939/1940) and geographical location, namely Alsace, and more specifically Bas-Rhin.

In addition to the lives of Alfred ZIMPFER, Elsa GRAETZ, Paul REBMANN and Lina WIEDEMANN between 1939 and 1945, I have also looked into the lives of Henri GRAETZ and Charles GRATZ, my paternal grandmother’s brothers, for whom I have found some interesting information, particularly in the case of Henri GRAETZ, to whom I will have to devote an article, as his life was so « special ».

The « Malgré-Nous » :

The term « Malgré-nous » refers to Alsatians and Moselle residents forcibly incorporated into the Wehrmacht, the regular German army, during the Second World War, whether in the Heer (army), the Luftwaffe (air force), the Kriegsmarine (navy) or the Waffen-SS. The female counterpart was the malgré-elles.

Alsace (minus the arrondissement of Belfort), part of Lorraine – the Moselle département as it is today – and a few villages in the Vosges département were ceded to the German Empire under the Treaty of Frankfurt, after the French defeat of 1871, leaving the population for a few months to « opt » for France. The populations of these regions who remained in France – in particular to maintain a French presence in the annexed zone – thus found themselves subjects of the German Emperor and subject to the obligations and customs of nationals of the new Reich. At the end of the war in 1918, after 4 years of military dictatorship, bullying and wilful destruction, the population of Alsace-Moselle no longer felt the slightest sympathy for Germany, and turned a blind eye in the hope of peace in the near future. They also became French again.

The problem was radically different in 1942, both sociologically and legally. From a human point of view, the young conscripts from Alsace and Moselle were not born Germans; for the most part, they remained « French at heart », and most of them did not opt for German nationality, which was automatically granted to them in the name of the Volkstum.

From a legal point of view, the de facto annexation of the three French départements by Nazi Germany was not ratified by international law, nor by any treaty between Vichy France and Germany.

Although the term « malgré-nous » (in spite of themselves) appeared as early as 1920, after the First World War, when associations of Alsatian and Lorraine veterans of the Great War used the term to highlight the fact that they had had to fight « in spite of themselves » in the German army against France, the first real « malgré-nous » (in spite of themselves) were forcibly incorporated by the German army from August 1942 onwards.

When the armistice of June 22, 1940 was signed, no mention was made of Alsace and Moselle. This territory therefore remained legally French, even though it was part of the German-occupied military zone.

The Nazi regime de facto annexed it to German territory, with a decree signed by Führer Adolf Hitler on October 18, 1940, prohibiting its publication.

The Vichy government confined itself to protest notes addressed to the German authorities of the Wiesbaden commission, but without making them public, fearing German reactions: « You understand, » Marshal Pétain told Robert Sérot, deputy for Moselle, in August 1942, « the Germans are sadists who will crush us if we make a move now. These notes remained unanswered.

The rumor then spread that a secret clause had once again handed Alsace-Lorraine over to Germany, with the difference that the three former French departments no longer formed a separate entity, as had been the case during the previous annexation. Bas-Rhin and Haut-Rhin became the CdZ-Gebiet Elsass, a territory attached to the Gau Baden-Elsaß, while Moselle became the CdZ-Gebiet Lothringen, a territory attached to the Gau Westmark on November 30, 1940.

Until August 1942, however, while paramilitary organizations multiplied, obliging the youth population to join, the ultimate legal transgression was refrained from: compulsory mobilization into the German army. Better still, Germany proclaimed that it didn’t need the Alsatians-Mosellans to win the war, which it hoped would soon be over and victorious. We don’t need the Alsatians to win the war, » said one propaganda speaker, « but it is for the honor of your country that we insist on having you in our ranks.

Nevertheless, Goebbels’ staff actively encouraged young people from Alsace and Moselle to enlist, but to no avail. Only the sons of the German civil servants present seem to have answered the call, but there were less than a thousand for the two Alsatian departments. Gauleiter Robert Wagner, who was in charge of Alsace, was convinced that those he saw as newly reconquered brothers of the race would soon hear the call of their blood and feel German; noting the tiny number of voluntary enlistments, he concluded – not without cynicism – that young people were reluctant to join the German army « for fear of their families », and that they would be happy to be forced to do so.

In the spring of 1942, in Vinnitsa, he persuaded the initially reluctant Adolf Hitler to introduce compulsory military service in Alsace, which was officially done on August 25, 1942.

The « Malgré-Nous » Paul REBMANN & Lina WIEDEMANN :

My maternal grandfather Paul Rebmann was hit hard by this compulsory draft order, and found himself drafted into the army of the Third Reich on May 22, 1943, to fight on the Russian front.

Although he was already seeing my grandmother Lina Wiedemann, marriage was no longer on the agenda from August 1942, and even less so in May 1943.

He had tried to flee the Bas-Rhin to the north-west (Sarrebourg) as early as May 1940, by bicycle, with his cousin Georges Brenner, accompanied by the priest of Bischwiller, as he recounts at the beginning of his book « Mémoires de Guerre », but without success. The German army had already reached the gates of Saverne, and they had to turn back, hearing artillery cannon fire in the distance.

As soon as he was drafted in May 1943, he was sent to the Russian front, in what is now Belarus. Between late October and early November 1943, he was stationed not far from Moguilev, as the Wehrmacht tried to take a village there, under fire from « Stalin’s organs ».

As he recounts in his memoirs (translated from Alsatian by Claudine Drago and reprinted in Laurent Pfaadt’s excellent book « Nous étions des Malgré-Nous »):

« We were very early in the morning, about a hundred meters from a village. Everyone was running, and I felt terribly alone. I could hear the bullets whistling. Shots were coming from everywhere, left and right. There were bodies lying on the ground. Our superiors didn’t care about the bodies, about all those lives lost, the main thing for them was to take the village by storm! Russians were occupying the houses and dying before our very eyes. Despite the horror, we were starving, but there were no orders to eat our rations. I was so hungry that I couldn’t resist rummaging through the backpack of a dead Russian to find even the smallest piece of dry bread. I was ashamed, but you can’t imagine what human beings are capable of at a time like this! »

Shortly afterwards, he managed to escape, deserting the Wehrmacht and surrendering to the Russians. From December 1943 onwards, he was held in Tambov Prison Camp 188, which he didn’t leave until the end of the war, in late November 1945.

After his release from the Tambov camp, Paul spent some time in Berlin for medical reasons, in order to regain sufficient strength to return to his family. On arrival in Berlin, Paul weighed just 36.5 kg. He finally arrived at the Reuilly military center on November 26, 1945, and Mr. Roussillon sent a telegram to Paul Rebmann Sr. to inform him of his son’s return.

For details, please consult the article: PAUL REBMANN (1921-2016) : MY MATERNAL GRANDFATHER

Alfred ZIMPFER & Elsa GRAETZ :

As far as my paternal grandfather is concerned, I haven’t found a single document to show that he was active in WW2, either as a « Malgré-Nous » or in the Resistance.

Perhaps the fact that he had already been married since 1938, and had a family, spared him this compulsory draft.

For details, please consult the article: ALFRED ZIMPFER (1907-1968): MY PATERNAL GRAND-FATHER

The Resistance Fighter Henri GRAETZ and the « Malgré-Nous » Charles GRAETZ :

My paternal grandmother’s two brothers had diametrically opposed careers during this conflict.

Like my grandfather Paul Rebmann, the young Charles GRAETZ, born in 1909 in Bischwiller, was drafted into the Wehrmacht after August 1942 and also sent to the Eastern Front.

However, he was much less fortunate than my grandfather, as he was killed on November 4, 1944, in Poland, near the village of Pokrzywnica.

According to his file on « Mémoire des Hommes », he was recognized as « Died for France » at the age of 35.

His brother Henri GRAETZ had a much more atypical career, as he served in the Resistance, but not in France.

According to the data we found, before the outbreak of war, he lived in Saigon (Hô-Chi-Minh-Ville), in French Indochina.

In December 1941, he was ordered to enlist in the Free French Forces. His main assignment: the domestic resistance within the « Graille network » (Source: Liste Ecochard).

Clearly, he escaped unscathed, as his marriage in 1946, still in Saigon, to Jacqueline ABRIAL, and his death in 1989 in Nyons in the Drôme, are all traceable.

Laisser un commentaire